Sermon - Dec 14, 2025 The Prophet Mary

The Prophet Mary

Luke 1:46b–55

Third Sunday of Advent, December 14, 2025

Rev. Heather Carlson

I grew up not knowing very much about Mary, Jesus’ mother. I knew who she was, of course. She appeared on countless Christmas cards. She showed up in the Sunday School pageant. She was always pretty, always quiet, always wearing pale blue. But beyond her appearance cradling a baby on Christmas Eve, I never really thought much about Mary.

That changed early in my ministry, when mentors encouraged me to spend time in a place outside the economic and political stability I had grown up in. An opportunity came to travel with a group of about fifteen young adults from churches across British Columbia and Alberta to Guatemala for nearly two weeks with GATE—Global Awareness Through Experience.

GATE was a program created by church partners to foster understanding of another culture and its realities through people-to-people connections. We were invited to approach the people we met not as tourists or helpers, but as pilgrims—deeply respectful of their culture, their history, and the gift of learning from them.

We began our time in Guatemala City, meeting human rights advocates, historians, poets, and families living precarious lives in temporary encampments. It was an immersion into Guatemalan history and culture, meant to help us understand how global economics and politics shape everyday lives in this sister North American country.

Guatemala lies just south of Mexico, in the same time zone as Saskatchewan, with a population of more than 18 million people. Its history stretches from the ancient Maya civilization through Spanish conquest in 1524, colonial rule, independence in 1821, and cycles of reform and repression.

Its recent history, however, is marked by a devastating rupture. In 1954, a U.S.-backed military coup overthrew a democratically elected president who had pursued land reforms that threatened wealthy landowners and the American-owned United Fruit Company. What followed was a succession of right-wing military dictatorships that rolled back reforms and violently crushed dissent.

This ushered in a brutal, U.S.-funded civil war that lasted thirty-six years, from 1960 to 1996. During that time, government forces carried out atrocities and genocide against the largely Indigenous Mayan population. With chilling disregard for human life, de facto president Efraín Ríos Montt declared that he would “drain the lake to kill the fish.” More than 200,000 Guatemalans were executed—by their own army. The effects are long-lasting. Our PCC still works in Guatemala to support education, income generation, food security, and women’s empowerment in the region.

After a week in the capital, we travelled into the highlands. Our first destination was the village of Zaquelpa. It is not a tourist destination. It is not even on most maps. But its story mirrors the story of many villages across Guatemala.

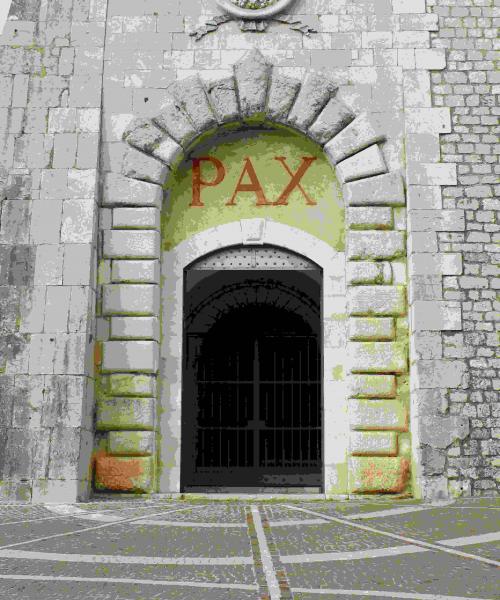

There we met Sister Annalise. She was in her mid-twenties—just one year younger than I was at the time. She greeted us inside a vast Catholic church built centuries earlier so that the entire town could gather inside. The church dominated the market square, surrounded by small one- and two-room homes.

In the early 1980s, the Guatemalan army seized this church. They gutted the interior, beheaded the statues of the saints, and chopped the crucifix into pieces. They turned the sanctuary into military barracks.

Over the following years, terror reigned in Zaquelpa. We walked beneath eucalyptus trees in the courtyard where men were tied up while they awaited interrogation. The Sunday School rooms became torture chambers. If interrogators did not get the answers they wanted in one room, prisoners were sent to the next—and the next—each one more brutal than the last.

Finally, captives were taken to a room no larger than our church nursery, where they were tortured to death. Though the war had ended six years earlier, the hooks were still visible in the rafters. Bloody handprints still marked the walls. As we crowded into the room, I sat beside the trap door in the floor—used to shovel out the blood.

We asked Sister Annalise how many people were killed there. She replied quietly, “Thousands.”

And yet this room is not a shrine to death.

After the army left in the 1990s—burning the sanctuary as they went—the people reclaimed their church. They rebuilt the roof. They refurbished the interior. And on the front wall, in bright construction-paper letters, they placed a prayer:

“Holy Spirit, come to your people.”

The torture rooms once again became classrooms and youth spaces. And the room of genocide became a prayer chapel.

They took the broken crucifix and pieced it back together. At the foot of the cross are small, simple crosses—made from Popsicle sticks—each bearing a name. These are placed for family members whose whereabouts are still unknown.

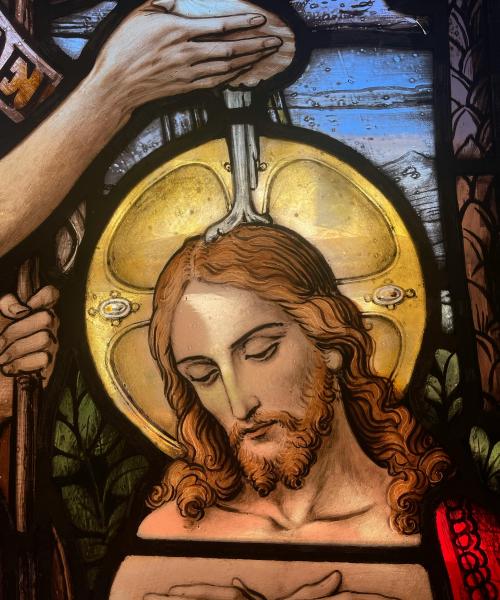

And beside those crosses stands Mary.

But not the Mary of my childhood. Not pale-skinned. Not dressed in soft blue. This Mary is Indigenous. She wears the bright, woven colours of traditional Mayan clothing.

This is the Mary of Luke 1:46–55. This is the prophet Mary.

In the very room where the state declared them worthless and expendable, the people of Zaquelpa proclaimed her song:

That God shows mercy.

That the lowly are lifted up.

That the hungry are filled with good things.

That the proud are scattered, and those who exploit the poor for their own gain, will be brought low.

This is Advent Joy. It is not simple cheer. It is closer to defiant hope—perhaps even wounded expectancy. When the world is in pain, this Sunday of Joy can sound almost cruel, unless we understand joy differently.

Joy, here, may be:

-

the refusal to say that suffering has the final word

-

the quiet insistence that God enters history as it is, not as we wish it were

-

a fragile light that proves the dark is not total

Mary is only quiet and polite if we refuse to hear her. Her song is a radical vision of reversal—a promise that justice will be done. She is less like the tender, mild Mary of Silent Night and more like Martin Luther King Jr., thundering, “I have a dream.” More like Isaiah proclaiming:

“Say to those who are of a fearful heart,

Be strong, do not fear!

Here is your God.”

The child born in a manger will grow to proclaim good news to the poor and the oppressed. He will scatter the proud, pull the mighty from their thrones, and send the rich away empty.

That is the story of Mary’s child.

It is the story the faithful in Guatemala told one another: Things must change, because God is a God of justice. And they would say, change comes like this: the work of ants—each one doing a little bit. Sister Annalise said there are not enough psychologists in the world to listen to our pain, so we come together to make tortillas, and slowly learn the work of trusting one another again. We sing as we work and encourage each other. We gather to pray, and open our hearts to the only one who can heal us.

Advent joy does not require us to look away from suffering or to distract ourselves in the face of oppression. In recent days, our province has announced deep, life-threatening cuts to supports for 77,000 people with severe disabilities. Children facing abuse for gender identity issues have been legislated exposure instead of protection. Our public medical and educational resources are being stolen for the wealthy. And the powerful strip human rights and tout flagrant lies.

The Church named this third Sunday Gaudete—Rejoice—not because the world has stopped hurting, but because it has not, and yet God is said to be drawing near anyway.

Sometimes joy interrupts sorrow; it does not replace it.

Lighting the rose candle is not a call to false happiness.

Sometimes the most honest Advent joy sounds like this:

The world is broken. And God has not abandoned it.

So, on this third Sunday of Advent, we do not rejoice because everything is fine. We rejoice because God has chosen to dwell in a world that is not. We rejoice because the Holy Spirit still comes to God’s people—into ruined sanctuaries, into wounded bodies, into frightened communities, into hearts that know both grief and hope.

Mary’s song reminds us that Advent is not passive waiting. It is holy expectation. It is learning to live as if God’s promises are already true, even when the evidence feels thin. It is joining the quiet, faithful work of ants—small acts of courage, truth-telling, generosity, and resistance—trusting that God gathers these fragments into something more than we can see.

In a world that tells us to harden our hearts, Mary teaches us to keep singing. In a world that declares some lives expendable, she dares to proclaim that the lowly are lifted up. In a world that knows torture rooms and mass graves, she points to a God who is born among the poor, executed by the powerful, and raised by love stronger than death.

So we light the candle. Not because the darkness is gone, but because it is not all there is. Sing, even if your voice trembles. Hope, even if it feels defiant. For the child Mary carries is already on the way, and God’s justice—slow as ants, stubborn as love—is still moving through the world.

St. John's

St. John's